“I am a great sinner, and Christ is a great savior!”

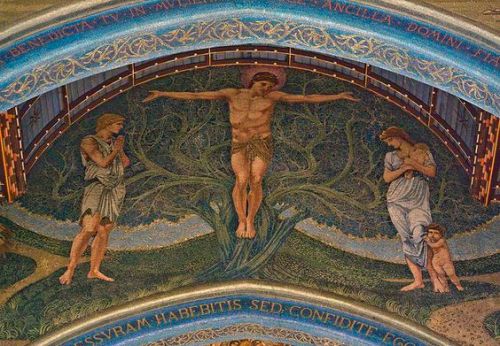

(“Christ on the Tree of Life”, mosaic by Edward Burne-Jones, 1894.)

It was my great privilege to preach yesterday at the Church of St. Michael and St. George in St. Louis, Missouri. How delightful to be with that wonderful congregation on such a meaningful day! The Rev’d Andrew Archie and his clergy colleagues, the Rev’d Blake Sawicky and the Rev’d Ezgi Saribay, extended me such warm hospitality on a snowy Ash Wednesday. The staff and parishioners were so kind in their welcome. The music, conducted by Dr. Rob Lehmann, was sublime.

A Sermon Preached on Ash Wednesday, February 10, 2016

By the Rev’d Canon Dane E. Boston

Texts: Joel 2:1-2, 12-17; 2 Corinthians 5:20b-6:10; Matthew 6:1-6, 16-21

May I speak in the Name of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. Amen.

“I am a great sinner, and Christ is a great savior.”

Those words were written by an 18th-century sailor, slave-ship captain, Christian convert, Church of England priest, and hymn-writer named John Newton, most famous for penning the lyrics of “Amazing Grace.” Nearing the end of his long life, with his health broken and his eyesight grown dim, Newton told a friend, “My memory is nearly gone, but still I remember two things: that I am a great sinner–and that Christ is a great saviour!”

Standing before you as a guest preacher this Ash Wednesday, I take Newton’s words both for my introduction to you and for the starting place of my sermon. I am tremendously grateful to the rector for inviting me to preach today. But I am also keenly aware of the fact that I don’t know you, and that you don’t know me–or at least, you don’t know me apart from whatever Father Sawicky might have told you about me, in which case I am tremendously grateful you didn’t stay away from church today.

Seeing, then, that we are strangers to one another, I have resolved to stick to what I can know–what I do know: “That I am a great sinner, and that Christ is a great savior!”

For you see, that announcement–that declaration–is really what this day is all about. On this day, the Church exhorts her members both corporately and individually to “lament our sins and acknowledge our wretchedness.” On this day, we are called to claim with one voice John Newton’s self-summary–we are invited, each of us and all of us, to say, “I am a great sinner, and Christ is a great savior.”

And that is what makes this day so difficult. To confess our sins–to own up to the fact that we’ve done wrong–isn’t necessarily hard for us. We do it every Sunday at the Holy Eucharist, and daily at Morning and Evening Prayer. We know we are guilty of faults and offenses–that we have sinned in thought, word, and deed, against God and against our neighbors. We know we have gone wrong, both by our actions and by our inaction–by what we have done, and by what we have left undone. We know we have sins to confess.

But Ash Wednesday goes deeper. On this day, we do not simply confess our sins–we confess that we are sinners. On this day, we do not merely own up to those times and places when we have broken God’s commandments–we own up to the fact that, at all times and in all places, we are broken creatures. On this day, we do not just cry out for forgiveness, asking that we may be set again on the narrow path–rather on this day, we cry out for salvation, acknowledging that apart from God’s grace we are lost no matter the path we tread; admitting that without the breath of God’s Spirit we are dead in our sins and trespasses; declaring that, until the Great Physician comes with balm for our hurting souls, “there is no health in us.”

This day dares to confront us, not simply the undeniable truth that we sometimes commit sins, but rather with the profoundly uncomfortable truth that we are sinners: that our hearts are hardened against the loving-kindness of God–that our wills have turned in on themselves to seek only our own drives and delights–that our very nature is fundamentally disordered by the problem of disobedience and the fact of Sin.

That’s why, when we come forward for the imposition of ashes today, we hear the words, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Those words carry us back to the very root of the problem. They are the words spoken by God to Adam after he and Eve have broken the commandment not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. By choosing to disobey the Lord’s only law, human beings lose their only true freedom. They become slaves to their own needs and appetites–their own devices and desires. They have no power of themselves to help themselves. And so God tells the dust-creatures who were made in his own image that that image will now be marred by mortality: “Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”

Now don’t for a minute get hung up on the historicity of that story, and worry about how a snake could talk or where the Garden of Eden might be located on a map. That story isn’t meant to explain things that happened long, long ago. That story is meant to explain things that happen now–each and every day–around us, and within us.

Why is it that we fall back again and again into behaviors we know are not good for us, for our souls or bodies, and are not good for our relationships with others? Why is it that I eat too much and drink too much, even though I know that temporary indulgence only leads to pain and unhappiness? Why is it that you tell lies even though you know they only serve to make your life more complicated and more difficult? Why is it that we continually look on other people as objects or obstacles or as the means to our own personal ends, even though we know that that leads only to the exploitation and degradation of God’s image in our fellow creatures?

“Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.” Today we hear again God’s words to Adam and we realize that they apply to each of us as well. The powers of Sin and Death are inextricably linked. The fact of our mortality and the problem of our continual disobedience are both wrapped up in the reality of our sinfulness. The ashes upon my head will declare what I cannot hide or deny–that I am indeed a great sinner.

But, dear people of God, that is not all that those ashes will declare. For mark the shape in which those ashes will be applied to each forehead in just a few moments. They may look like nothing more than a smudge. But feel the way that the priest’s thumb moves across your brow. If the ashes on my face carry with them the terrible reminder that I am a great sinner, they also carry with them the glorious announcement that Christ is a great savior!

For the ashes upon our heads will be imposed in the shape of a cross. The symbol of our sinfulness shows forth the sign of Jesus’ victory. The reminder of our mortality and brokenness also tells out the great Good News that God has not abandoned us or forsaken us.

For God “made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.” The Cross is the everlasting declaration of God’s love and mercy for the lost and the broken. The Cross is the eternal announcement of God’s power and promise held out to the sinful and the stained. The Cross is the undoing of the curse, the defeat of death by death, the conquest of sin by bearing the cost of sin, the destruction of disobedience by means of Christ’s ultimate obedience.

And so the next forty days are not, for us, days of grief and gloom–of dismal drudgery and disfigured faces–of weeping and wailing for our sins. For in this holy season of Lent, we carry our own crosses gladly as we follow the footsteps of Jesus. In the weeks to come, we ready our hearts to hear again the story of what God has done for the sake of people such as we are–for sinners like me and like you. As we approach once more the contemplation of those mighty acts by which God has won for us life and salvation, we go joyfully to Jerusalem, to see sin silenced by the One who would not open his mouth; to see death vanquished by the One who humbled himself even unto death upon the Cross; to see the gracious gift of everlasting life flowing from the open-door of the empty tomb.

So let us, then, make a right beginning of holy Lent. Let us own the announcement of this Ash Wednesday. Let us, each and all, boldly, joyfully, gratefully, humbly declare, “I am a great sinner, and Christ is a great savior.” AMEN.